12 Favorite Recent Films (+ Eurotour Dates!)

Best new-to-me films in 4 genres, everywhere from Palestine to Providence

First off, I’m going on tour, babyyyy! Please do send along this flyer to any comrades in any of these cities. Help me fete Antifascism and the Avant-Garde! Some of these are traditional book talks, and some are more flexible and connected to film screenings. One is even on my comics work (Amsterdam). Hope to see some of you there!

Now, onwards to my favorite watches of the last two months, split up into 3 overarching categories.

Irony, Absurdity, and Social Realism

Why is it that irony and social realism pair so beautifully with one another? Is it that humans require dark humor to make heartbreaking tragedy palatable? Or is it the only possible ethical response to horror? The existentialists would have a field day. So would Antonin Artaud. But it’s not an accident that both the short An Orange from Jaffa, shortlisted for best narrative short in this last year’s Oscars, and Radu Jude’s 2013 Shadow of a Cloud, deal with truly horrifying scenarios: the occupation of Palestine, and a priest overseeing a death. Almughanni’s film tracks a Palestinian man, recently arrived from abroad, who is denied clearance at a checkpoint, and just wants to see his mother. To his enormous credit, the filmmaker doesn’t dwell in the melodramatic. The situation is absurd and horrifying enough, and the banality of events portrayed land that much more affectively in a social realist tone. Jude’s film, rather, is cringe comedy as its best: an exhausted priest-for-hire deals with a ridiculous family around the death of their matriarch. It doesn’t have the political punch of some of his later films (see below on another recent favorite), but shows, as with his recent Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, the absolute indignity of modern existence. It’s the only film in recent memory in which I’ve truly empathized with a priest.

Music Video Cinema

I’m fascinated by a recent tendency in film that I’d like to call music video cinema— films that are carried by the songs within them. There’s another blog post in the work about them, but many documentaries and fiction films in recent years feel like a string of music videos pulled together. This, however, isn’t criticism. In fact it’s one of my favorite genres. One need only think about Lovers Rock, the second, and indisputably the best and highest praised, episode of Steve McQueen’s 2020 Small Axe miniseries: the entire hour-long episode is a dance party, and the most memorable scenes span the length of an entire song. Think Contessa Gayles’s Songs from the Hole, which I’ve talked about many times on this Substack. Think Jenn Nkiru’s short films, or TT the Artist’s Dark City Beneath the Beat, a dance documentary. It’s not an accident that many of the films in this category revolve around Blackness and Afrofuturism: the music video film is at least as old as Sun Ra, and might be as old as film itself (see: Vertov). Sometimes the music video film is very literally a music, video, film: Mati Diop’s collab with Manon Lutanie shows a young dancer improvising to a song, wearing a blue suit. Sia’s Chandelier music video immediately comes to mind, but Diop’s Naked Blue captures the enthusiasm and youth of teen dancer Oumy Bruni Garrel with empathy and rawness. Of course, there’s a film like Sinners, which really wouldn’t get the enthusiastic response that it did without its music, especially the 15-minute long orgiastic musical sequence that forms its climax. And then there’s Larrain’s Maria, in which Angelina Jolie plays the opera diva superstar Maria Callas. I am a bit of a Larrain apologist, even when he is a bit of a one-trick pony, focusing on problematic and slightly insane charismatic women (Ema, Jackie, Spencer, etc). Maria wouldn’t work without the music, and that’s entirely ok.

Fresh Takes on the “Documentary”

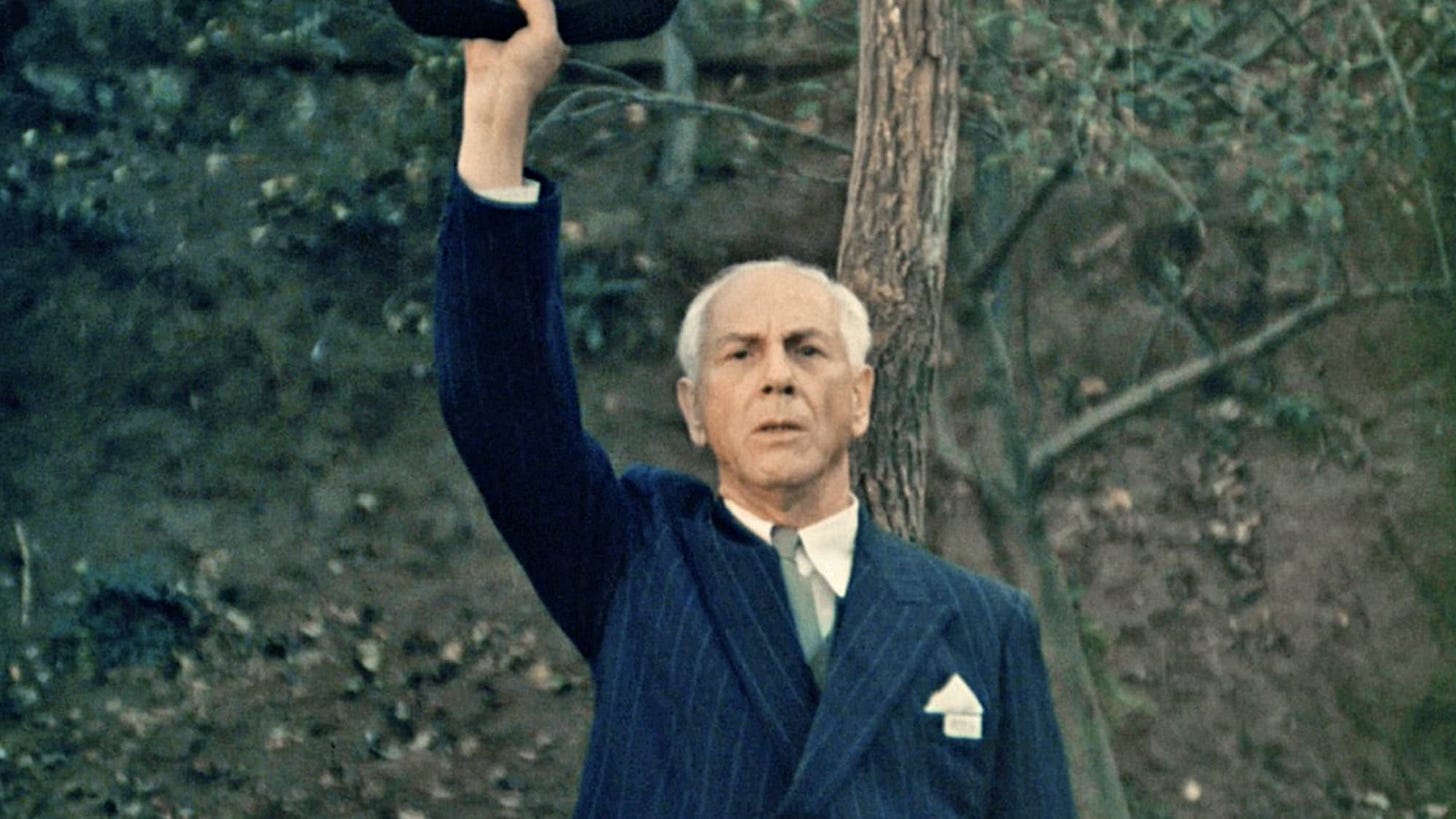

I compulsively put quotation marks around “documentary” to show that the genre is really not as separate from fiction as we would like to think. My favorite documentaries are those that revel in the fictionality inherent to the medium. My book is all about this drive for truth-telling through a “laying bare the device”— something documentaries have been doing more and more frequently in recent years. Secret Mall Apartment, about, well, a secret mall apartment (created and squatted in for several years by artsy punks in early 2000s Providence, RI), does this beautifully. The director recreates the titular apartment and has its previous occupants experience it anew— a kind of nicecore version of Nathan Fielder’s The Rehearsal, but instead of rehearsing, it’s a tender recreation of a lost era. Speaking of tenderness: Dónal Foreman’s 2018 film about his estranged father, The Image You Missed, broke me in ways I hadn’t experienced in many years. I met Dónal briefly at a semitext(e) event in LA (I have never been cooler than this night, when I also met my idol Chris Kraus!) and finally checked out his films when they were streaming on Criterion. A personal documentary in the Vardaian vein, with a deep vulnerability: what to do with a father who is so great politically (he filmed the Troubles in Ireland and was pro-IRA) but, honestly, a piece-of-shit personally? (Relatable, I think, to many leftits grappling with similar issues). On the note of politics: Jude’s short The Marshal's Two Executions has a simple conceit which is quite experimental in practice: showing the execution of General Ion Antonescu, a Nazi sympathizer who has recently been revived as some kind of national hero in Romania. Jude plays the actual newsreel footage of his execution alongside a romanticized, nationalistic portrayal from the 1990s, showing the subtle and not-so-subtle manipulations at play in a Chris Markerian bent. (This footage and concept overall would recur in I Do Not Care If We Go Down in History as Barbarians, which I consider Jude’s best film). Finally, there’s The Encampments, which I think is a really stunning example of activist cinema, despite some of the legitimate criticisms I’ve heard. It has none of the formalist play of the earlier films on this list, but it would only distract from the importance of the message.

Romantic Comedies

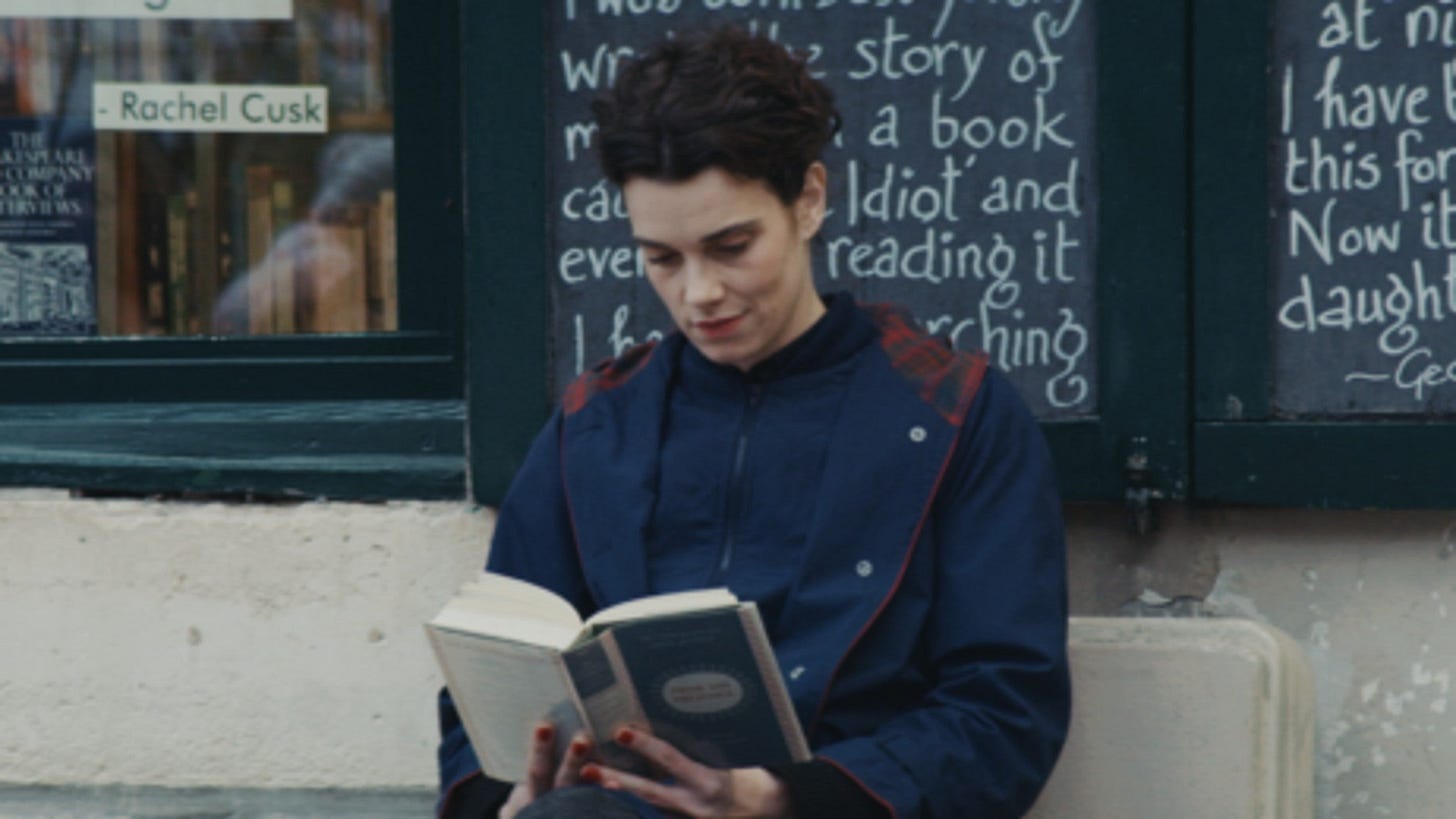

Sometimes, I just need a nice ol’ palliative rom-com. I constantly talk about how mumblecore is my comfort genre, so my favorite rom-coms are either from the 1980s or snarky comedies (I recently came across a love letter to Easy A after seeing it in theatres in its first weekend of release, and will continue to defend it, and Bring It On, to my deathbed). Crossing Delancey is somewhere between Moonstruck and When Harry Met Sally, and might be one of the most Jewish films I’ve ever seen: Amy Irving, bookstore worker and member of the New York literati, has to choose between an exotic poet and… a pickle salesman (Pickleman?). I’ve since recommended it to several friends. Truly a balm to the wounded diaspora. Meanwhile, my buds B and R recommended The Birdcage to me, which I (shockingly!) had never seen. It is more com than rom but, my god, are there incredible one-liners. (“Real men schmear!” “It’s always poor Mrs Coleman!” “Bob Fosse! Martha Graham! Madonna! Madonna! Madonna!”) You all probably already know the plot, but Nathan Lane and Robin Williams, a gay couple, have to convince their son’s fiancee’s family that they are straight. Hijinks ensue. This movie is a joy. Finally, Jane Austen Wrecked My Life is probably the closest thing to an actual rom-com that I’ve seen in theatres in the last few years. It happens to be French. It happens to be partially set at Shakespeare Company in Paris. Like Crossing Delancey, it’s also kind of about autonomy, trauma, and the joy (and pain) of writing. It isn’t really about Jane Austen (which, for an Austen-phobe like me, means the film is all the better for it). It’s another lovely balm of a film. And still in theatres!

Until next week! Happy watching, xo-J

![Maria — Pablo Larraín [Review] | In Review Online Maria — Pablo Larraín [Review] | In Review Online](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!THZL!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F42cb7a37-30da-4c1b-983e-8d08623dce6c_768x434.jpeg)