Hello subscribers, just sending along a list of my favorite new-to-me films from the last month. Apologies this comes a few days late— I spent the weekend watching upwards of 20 (!) films at the Blackstar Film Fest in Philadelphia, one of the largest film festivals exclusively devoted to films from BIPOC filmmakers. My post on that fest is (probably) coming up next week and I have thoughts! Until then:

1. Hal Ashby, Being There, 1979

I love a Magritte-inspired aesthetic, and was pleasantly surprised that the tone of the film did feel very resonant of a Magritte painting overall. The plot seems a bit reminiscent of Forest Gump, but is much more thoughtful, surrealist, and interesting. Generally, the film is about an intellectually challenged gardener who is so used to his routine and surroundings, cooped up in an enormous old money estate, that when his boss dies he is left with no ability to fend for himself. He does, however, have manners, and the East Coast rich are sequestered and idiotic (and racist) enough to assume his intelligence and good breeding. Political, tender, funny, heartbreakingly sad. It left Criterion but I believe you can watch it on AppleTV/iTunes or rent it on a variety of platforms.

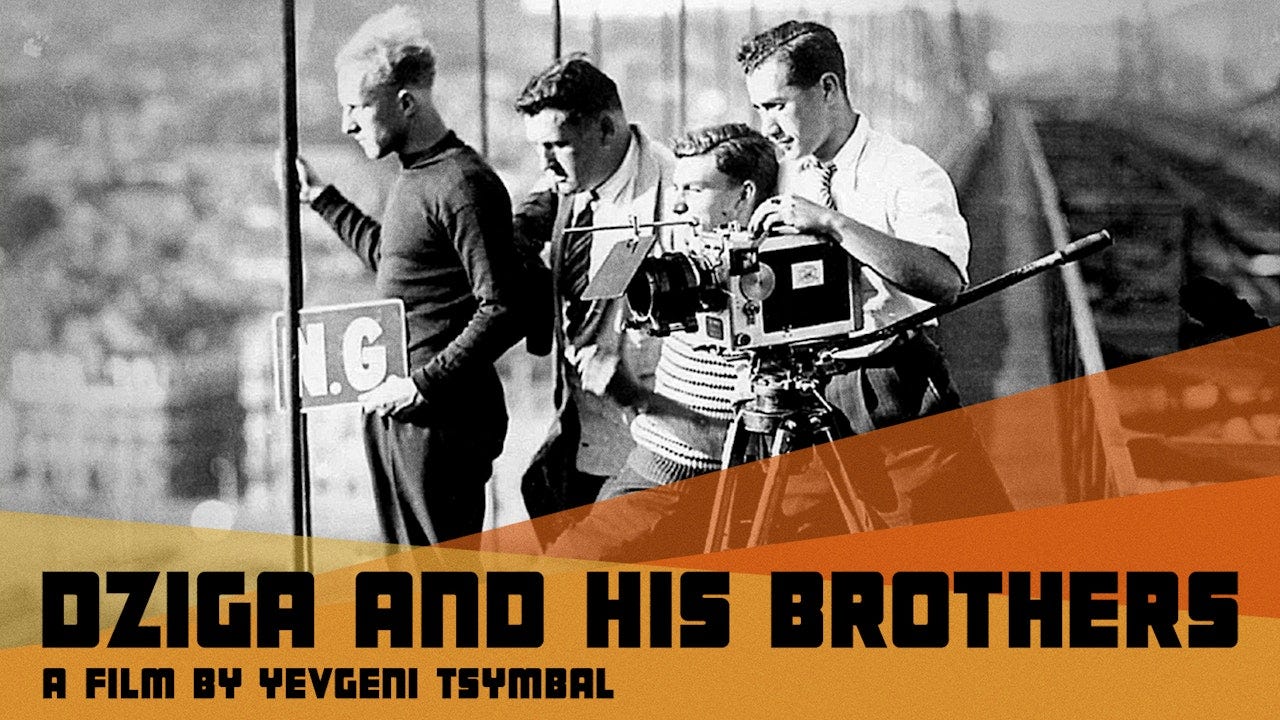

2.Evgeny Tsymbal, Dziga and His Brothers, 2002

Excellent (if a little cloying) post-Soviet Russian documentary on Dziga Vertov (né Denis Kaufman) and his brothers Mikhail and Boris Kaufman. Even for someone who wrote the bulk of their dissertation on Vertov, I learned quite a few things about Mikhail and Boris, especially towards the end of their lives! For those who don’t know: all three brothers became world-renowned filmmakers. Mikhail Kaufman’s In Spring (1929) is particularly gorgeous. Boris Kaufman ended up working with Jean Vigo in France and later as a cinematographer in Hollywood. This Russian-language doc serves as a wonderful and captivating introduction to their lives, although it falls prey to many of the pitfalls of the Russophone “poetic” documentary… namely: over-psychologizing and romanticizing its subjects, playing somewhat fast and loose with history, and not addressing certain political discrepancies in favor of legibility. Namely, there were hints but no discussion of the ideological difference of Boris (who lived in France and then worked with Elia Kazan for On the Waterfront, acquiring quite a few awards, including Oscars!), and Mikhail & Dziga’s communist beliefs. As a biographical account, though, this is the best I’ve seen on their work! See it on the Criterion Channel.

3. Gen Nagao, Motion Picture: Choke, 2024

I got to spent several weeks checking out films at Japan Cuts, the largest contemporary Japanese film festival in North America. This was one of the first films I saw at the fest, and it stuck with me. While not a perfect film, the conceit is fascinating: a post-apocalyptic narrative set in a world in which humans devolved back to prehistoric times, and before the invention of language. There have been so many post-apocalyptic films coming out over the past year (for quite obvious reasons), but it’s rare to find something so playful and fun, if also horrifying. The film is entirely in black-and-white, and the cinematography is experimental without being over-the-top (which can tend towards student film-esque). Really I was the most captivated by protagonist Wada Misa, whose expressive, humorous, and emotive acting I could have watched all day.

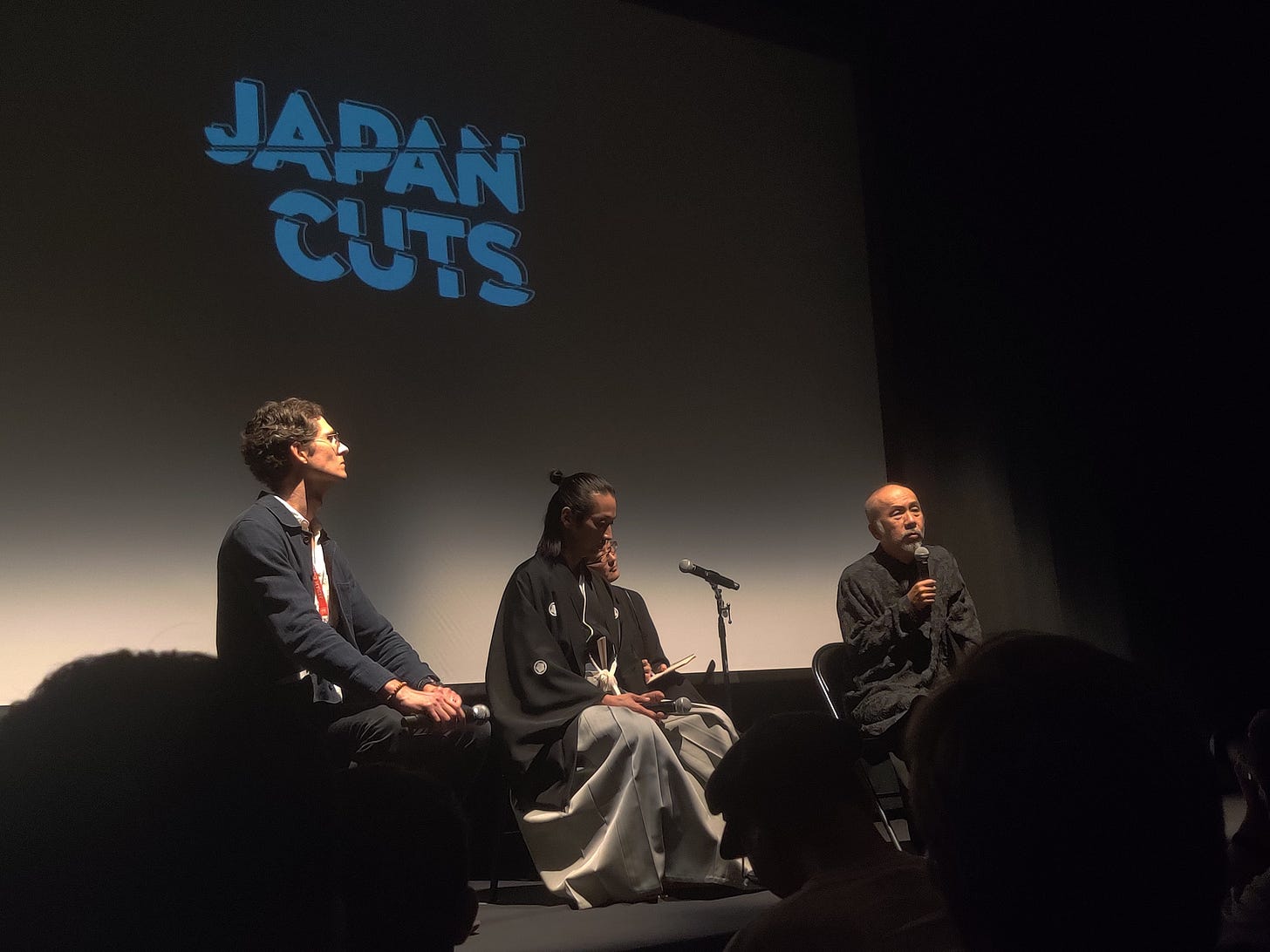

4. Tsukamoto Shinya, Shadow of Fire, 2023

The absolute stand-out of the fest was this, the latest film of the “war trilogy” of Tsukamoto Shinya, best known as the director (and star!) of Tetsuo: Iron Man (1988), a film that I genuinely thought would get me fired when I taught it in my Japanese Cinema class last fall. (Just google: Tetsuo drill penis, yikes). Tetsuo is one of my favorite films of all time, and while his war trilogy (including Killing from 2019, which is also excellent) is aesthetically nothing like the manic stop-motion scrap metal punk of the Tetsuo films, it is breath-taking. Tsukamoto is one of the few renowned resolutely antiwar, vocally antifascist filmmakers in Japan today. So much more can be written on the war trilogy, especially on the way it “keeps the fear of war alive,” in the words of Victor Shklovsky from 1917. The film is about the way the immediate aftermath of WWII in Japan caused a variety of deeply horrifying and embodied traumas onto many people: here, a sex worker, several former soldiers, and an abandoned young child-turned-thief, through whom we view most of the other characters. No other filmmaker can make an antiwar war movie quite like this. Here is a great intro to the film by Steve MacFarlane.

5. Edward Yang, Mahjong, 1996

I love Edward Yang. I love his more serious films (Taipei Story, The Terrorizers), but I also love (perhaps with slightly less enthusiasm) his dramedy spoofs from his “New Taipei” trilogy. The trilogy generally focuses on negative effects of unfettered capitalism on Taipei, and the way Americanization and corruption wreaks havoc on society. The film is hard to describe as anything but a screwball comedy, and largely follows a rowdy gang of young ne’er-do-well men (some of whom are outrageously wealthy, some who are poor), as they try to amass money, sleep around, and grapple with their often similarly ne’er-do-well parents. As with many of Yang’s films, most of the characters are somewhat hateful (although charismatic), and a select few, though flawed, form the emotional core of the film and end up reliable cyphers for the audience and filmmaker. Currently I’m not seeing any way to see this at home so if you see a screening in theatres, I highly recommend!

6. Radu Jude, I Do Not Care if We Go Down in History as Barbarians, 2019

I already wrote a bit about this brilliant film in my last post, but my god I love this film, and all the films by Jude, so much. Yet another wonderful entry into the antifascist film canon (maybe I will write a chapter on this film in a future book at some point? hmm…) If you like experimental form and leftist politics, this film is for you, as its experimental form is its politics. Don’t let its long run time fool you— every minute is captivating. You can view it on OvidTV, Kanopy, or Klassiki (a streaming service for Eastern European film).

7. Irina Tsilyk, The Earth is Blue as an Orange, 2020

Extremely touching (but not corny or melodramatic!) documentary about a family in Russian-occupied Donbass, and especially a teenage girl learning photography and cinematography. The girl interviews her family and friends and works with her mother in an attempt to communicate, cinematographically, how it feels to live in a warzone. Like almost all my favorite docs, it’s highly reflexive and thoughtful about the power of filmmaking itself. In my favorite scene, the girl and her family watch Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera for inspiration!! (This is also the scene referenced in the image above) Wow. It’s available on Amazon Prime and rentable on several platforms.

8. Sergei Loznitsa, Donbass, 2018

Loznitsa is much better known these days for his documentaries, which encompass more typical vérité-style films documenting a certain event (such as his excellent Maidan about the 2014 revolution in Ukraine), or (my personal favorite) his semi-documentary archival reconstructions, which create sounds to align with originally audio-less archival documents, usually of some kind of horrific event (The Trial, Babi Yar, etc). I was especially curious to check out his fictional film Donbass, and was surprised by how brilliantly he uses the fictional medium as well. Donbass is set between Russian-occupied Eastern Ukraine as well as Western Ukraine, and weaves a web of characters and situations highlighting the way Russian media can skillfully craft perceptions (truth and reality are constantly questioned, and the news becomes embellished and outright faked), as well as corruption endemic on both sides (clearly more on the Russian side, but also existing on the Ukraine side). A brilliant move from the film: each subsequent scene features a side character from the previous scene, creating a feeling of subtle cohesion that works skillfully and subconsciously on the viewer. Masterful. Watch it on Amazon Prime or rent it on several platforms.

9.Masumura Yasuzo, The Black Report, 1963

Masumura Yasuzo is one of those filmmakers that Japanese film professors are extremely familiar with, but who remains elusive to even the nerdiest of non-Japanophone or non-academic Japanese film buffs. He was an incredibly prolific filmmaker of what is unfortunately called the Japanese New Wave, aligned with iconoclasts such as Oshima Nagisa, but his films are still very hard to find in translation. I saw many of his films in Japan during a retrospective at an old theatre in Ikebukuro, but was very happy to revisit two of them on Mubi this past month. This one was my favorite, a noir-ish whodunit that is as critical of the legal system as it is of capitalism. (Another good one, the 1963 Black Test Car, is more critical of capitalism than The Black Report, but I thought this film was better and more cohesive overall). Sexy, complicated, dark, fast-paced. Masumura’s films usually aren’t my preferred taste from the Japanese 1960s, but this one was fun as heck. You can rent it on Amazon Prime or Apple TV, but Mubi also has three other Masumura films in its current collection if you’d like a taste of his style.

All for now! Hope folks are staying dry and cool. Here is an extra lil’ photo of Tsukamoto Shinya in the flesh (!) with Shadow of Fire actor and professional dancer Moriyama Mirai, in conversation with my friend Joel Neville Anderson (SUNY Purchase).