Music and (Revolutionary?) Nationalism

Introducing my seasonal playlist by opening pandora's box (read at your own risk)

“The point of the Jew is to be a thorn in nationalism’s side,” I thought to myself, brows furrowed, biking back from the restaurant on Tuesday.

I had just had dinner with three colleagues and friends, all broadly in Slavic and Central/Eastern European Studies. We were talking, as these things tend to go, about nationalism. The argument of my friend (I will call them S) was one I had heard before: that Ukrainian ethnonationalism was understandable, given that they are literally being attacked. The Russophobic mania in Ukraine— the banning of Russian language books, despite their liberatory politics, or ostensibly apolitical nature—made sense, even if it wasn’t necessarily something we could condone. “We must let it go, it’s understandable,” S said.

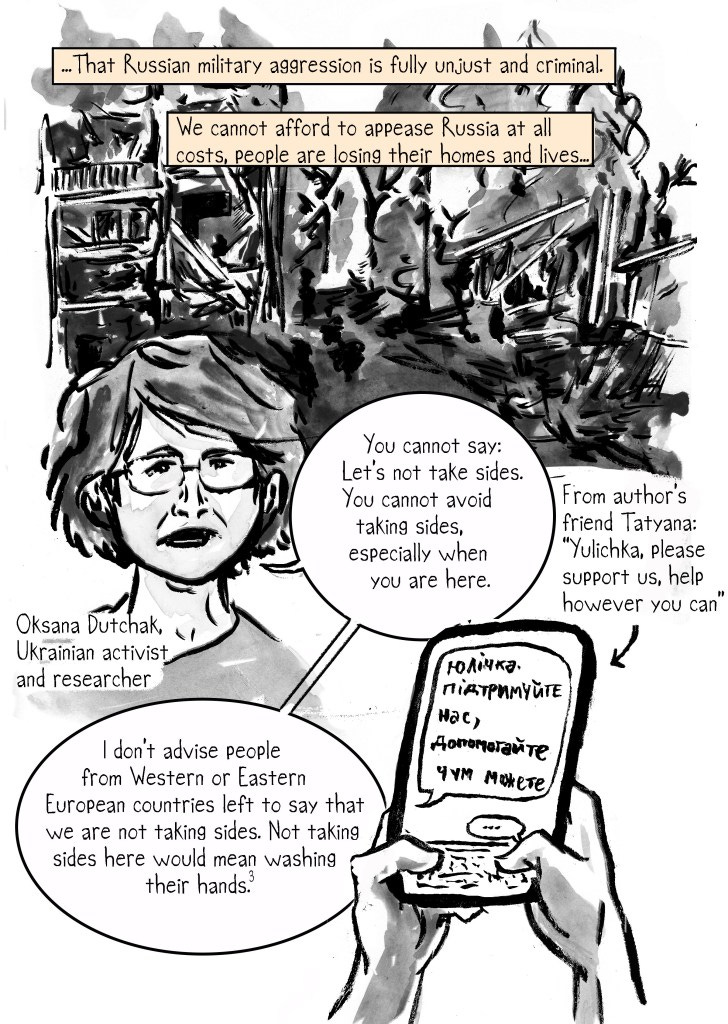

This was something the leftist Oksana Dutchak described in an interview with LeftEast, just a week after the invasion and war in Ukraine began:

The population got very anti-Russian now. By trying to make Ukraine the country under their total influence, they are doing the opposite thing because the majority of people are now very against Russia.

There are people who are not radically anti-Russia. But it is hard when you see what is happening, the bombing in Kharkiv – which is one of the biggest cities in Ukraine and a predominantly Russian-speaking city. The level of hate is very high now. It is explainable. It is hard in these circumstances to perceive Russia differently.

Almost two and a half years later, the level of hate remains, and is even more vitriolic. It is explainable, and understandable. But just because it is understandable, does it make it right?

I quoted other words by Dutchak in my March 2022 comic for the Nib. I wasn’t quite cherry-picking, but I certainly described the necessity for leftists to be in solidarity with Ukrainians against Russia.

The comic was ratioed (i.e. receiving more comments than likes) as soon as it appeared on the Nib Instagram account. I woke up to over two thousand replies, just a few hours after posting. Russian bots and leftists denounced the comic for being neoliberal, despite trying precisely to add nuance to the disturbing pro-Russian content I’ve been seeing on leftist social media accounts. This whole experience aligned with my first bout of COVID and I spent five days in complete mental and physical meltdown while trapped in a conference hotel, able to stomach nothing but bananas and saltines. Yet in the subsequent weeks and months, I was even more disappointed with the reaction my comic received from other Ukrainians, who saw me as Jewish, not Ukrainian, despite my entire biological family being from present-day Ukraine, as far back as our family history could go. Ethnonationalism reared its ugly head.

I relate this bit of old news because I was immediately reminded of the introduction to my forthcoming book (pre-order coming in one month!). I start the book by describing an experience at a folk concert of (at the time) my favorite band, a Ukrainian “ethnochaos” ensemble, just a few months later. I describe how the band used extensive imagery that showed the suffering of Ukraine, but also included Christian imagery and even some disturbing right-wing symbolism. I distinctly remember the horror of seeing the cross of St. George, and the an animated loop that demonstrated the tie between (ethnic) Ukrainians and the earth. I could not help remembering how the Imperial Russian government explicitly denied this tie to the earth for Jews and Roma; hence I became the first homeowner in my entire ancestral line. This tie to the earth was literally denied for Jews for millennia.

In my book I write:

Confusion, and then horror, set in. I was born in Kyiv and emigrated to the US in childhood, with the second wave of Jewish refugees from the USSR, now leaving a newly independent country embroiled in political chaos and swift economic collapse. Seeing the animated visuals behind my favorite band, I realized with growing horror that my ethnicity—euphemistically titled the piatyi punkt, or “fifth point” on the Soviet identification card, on which “Jew” was unceremoniously written—continued, even in the 21st century, to render me a perpetual Other: I could never be one of them. To be Ukrainian did not mean to live and breathe in a region, but to share a bloodline rooted in the soil. The Russian word for peasant is Christian.

I remembered these exact words two Wednesdays ago, at a concert of the Belfast band Kneecap (my favorite track of theirs is included in the playlist below). I was psyched to see the hip hop band, which raps almost entirely in Gaelic, after watching the eponymous film (and including it in my top films of the past month).

I skipped the openers because I was reading a part in a Bertolt Brecht play for my friend’s class (more on this in future posts), and was surprised to see that the TLA on South Street was packed to the gills, and the show was sold out. “This is great!” I thought. “Philly venues almost never sell out.”

As expected, the show was full of anti-British declarations, and as always, DJ Próvaí wore his characteristic Irish flag balaclava. This in itself would not have bothered me. Ireland has every right to hate the British for their long history of violence and genocide— of people, precious resources, environment, culture, and language. I was heartened that a significant number of audience members wore keffiyehs even in the venue’s sweltering heat, and near the end of the concert, the audience started a rousing pro-Palestinian chant.

I looked around. The vast majority of the audience was the absolute palest of the pale. Many looked uncomfortable during the chants and stared stoically ahead. Only a few knew Gaelic (I certainly didn’t). Disturbingly, I saw t-shirts with police insignia that immediately branded them as off-duty cops. I remembered that I saw the same thing at the aforementioned Ukrainian folk show: off-duty cops, enjoying the performance, yelling anti-Russian screeds. I remembered, also, that the many Philly fascists roaming the streets of Fishtown carrying police batons in June 2020 were Irish-American off-duty cops, protected by more on-duty cops. How many of them were here, I wondered, at this very show?

I talked about this a few days later, hanging out with my Irish-from-Ireland friend, whom I’ll call G, in Brooklyn. I asked their opinion on Kneecap— G didn’t like the band—and I expressed my discomfort with displays of Irish ethnonationalism, despite aligning with the band’s politics overall and liking their music. “I guess to be Irish these days you need to be nationalist by default,” G said, chuckling, with some obvious discomfort. I didn’t tell G my own experience with Irish-American ethnonationalism: an old boyfriend, half-Irish, blocking my entrance to a party that had been proclaimed “Jew-free”; the “Jew [cheap] whiskey” his family served on Christmas eve.

I thought about all this while at dinner on Tuesday, head-to-head with S about ethnonationalism. For S, who is Jewish as well as Eastern European, ethnonationalism is understandable when the country is being under attack. I vehemently disagreed, digging my heels in further. In my view, no ethnonationalism (indeed, no nationalism) can ever be condoned— even when said nation is under attack. My political views broadly fall in the spectrum of “communism with anarchist characteristics,” to paraphrase Sophie Lewis. I pressed on: we should aim for a world of no nations at all; to allow, as so many leftists have done worldwide, a temporary ideological alignment with nationalism in the service of liberation (i.e. “revolutionary nationalism”) is to open a portal to a black hole. Ethnonationalism cannot sustain itself without the eventual expulsion of the Other. (See: Israel, see: Palestine).

Eventually I backed down. I was getting overheated, and this was a work event. Fundamentally the argument was about the right of the victim to become an eventual oppressor (see: Israel, see: Palestine), and one with which I vehemently disagreed. Do the Sept 11 attacks justify the subsequent vicious Islamophobia, the hate crimes and “freedom fries,” even when millions of Americans genuinely felt under attack? Historically I’ve had trouble letting things go when something seemed intuitively wrong. I’ve been told that this is some kind of neurodivergence, and I don’t disagree. As I write in the intro to my book, on the Ukrainian concert: “a deeper, far more traumatized part of my psyche rang distant alarm bells.” This refusal to back down, this urge to show society its true face, its hypocrisy and complicity, precisely because it is uncomfortable to witness— this is the function of the black sheep. For me, it’s also what it means to be Jewish, perpetually a thorn in everyone’s side.

ANYYYway, TLDR; here’s my seasonal playlist, which includes my favorite Kneecap song. It also includes some of my most-listened-to new music from the past few months: Caroline Shaw, Kelly Lee Owens, Phantogram, and Glass Animals are especially beloved, among so many others. As always, please don’t listen on shuffle: the order here has a perspective, a thesis or argument, an unwinding followed by sharp edges, occasionally softened, and slowly dissipating. xo