On election night, I had a splitting headache. Truth be told I had emotionally detached from the whole debacle, although I did my civic duty and went to vote first thing in the morning, dog in tow. The Reclaim Philadelphia cheat sheet I brought with me to the polls wasn’t particularly enticing. There were no ballot measures, and, as in so many years, I voted a straight Democrat ticket down the line. I was unenthusiastic about any candidate save socialist state senator and DSA member Nikil Saval.

Last weekend I left Philadelphia to visit my friend Molly and her two kids in Cleveland. I wanted to spend time with them over Halloween, but I was also desperate to leave Philadelphia during the height of electioneering. There was something so depressing about the whole thing, the desperation, the peeling campaign posters, the unanswered phone calls and unreplied, screeching texts from unfamiliar numbers (parodied in a recent Tiktok), like the last dregs of democracy gasping for breath. The sad fact is that I preferred being in a more solidly Red state and wanted to avoid the madness.

My friends in Cleveland and I agreed that Trump would win, but that we didn’t realize just how quickly. I told them thought Kamala would lose for two reasons, based entirely on what the kids call “vibes.” And in Philadelphia, the vibes were not good. Reaons:

If I were to believe the graffiti in my neighborhood, the crustpunks were pro-Trump. The neighborhood ne’er-do-wells of this microgeneration were viciously anti-Democrat, and I don’t blame them. Seeing the pro-Trump tags made by the skater kids, I knew Trump was the “cool” candidate, the anti-status-quo, the fuck-the-system candidate. And that was just damn depressing.

The normie do-gooders couldn’t imagine Kamala losing. I knew this because of Merv. Every couple of weeks for the last year I’ve been getting allergy shots from Merv. Earlier this week I had an appointment with Merv. I seemed kind of nervous about the election, and while injecting microparticles of cat dander and dust into my arms, he said, “don’t you worry, Kamala is gonna win,” with enough confidence to power a small engine. Then he gave me two yellow pins that said “votes for women.” I stuck one on a backpack but was secretly relieved when it fell off.

Granted, these reasons are pure affect, an undefined there-is-just-something-in-the-air. And yet I was worried. And so, instead of spending the night at an election watch party, I was nursing a headache, eating handfuls of M&Ms and rewatching episodes of Sex & the City (neither of which probably helped the headache). I avoided social media and the news at all costs. When I woke up and looked at the phone, I had some idea of what I would find, but did not know how quickly, how definitively, and how soon.

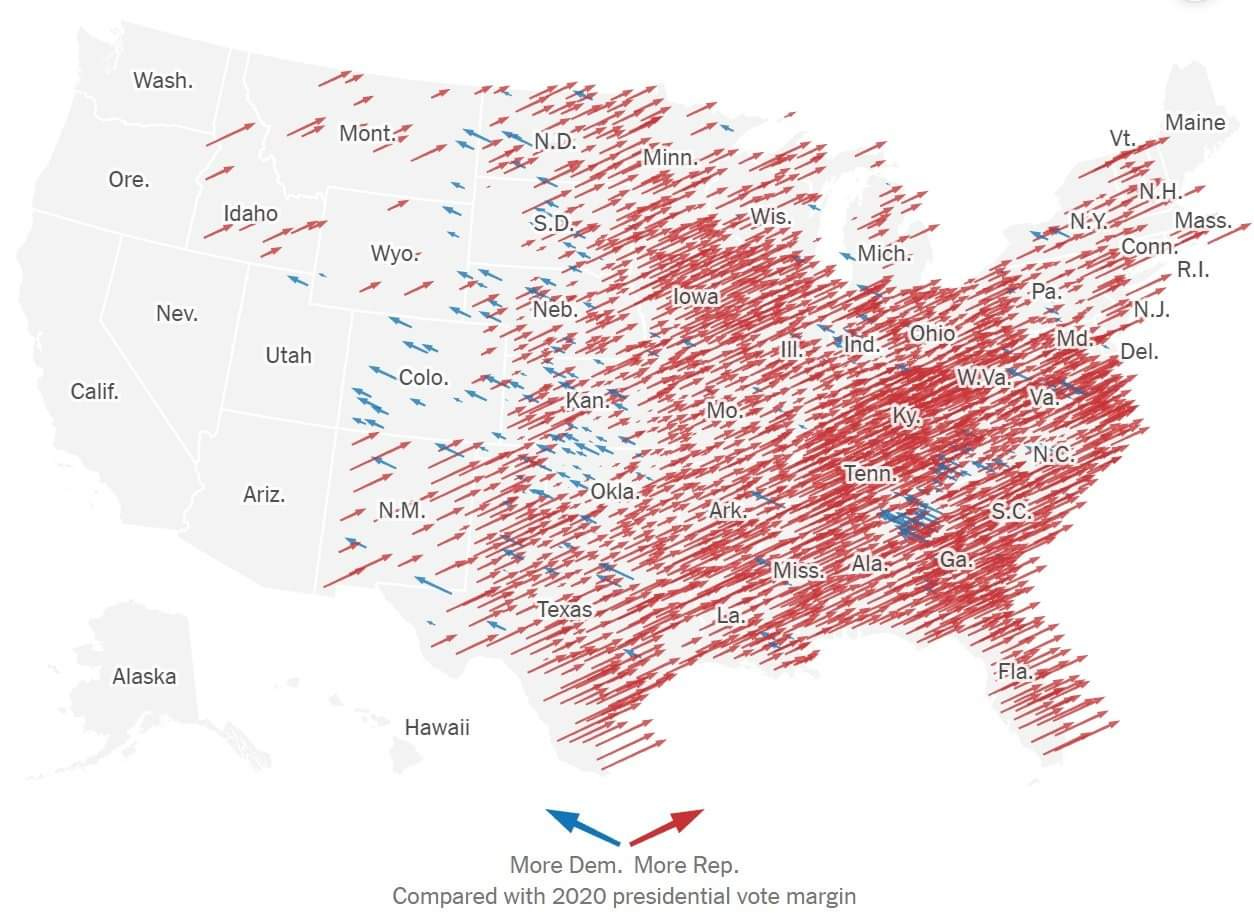

I mention this not to brag about my Cassandra complex, but to note that the fault of the election does not lie with the voters themselves. Indeed the Trump victory was definitive. As the below image shows, there was a massive swing to the right across much of the US.

Perhaps it is overly naive or optimistic of me, but I find it very hard to believe that over half of the country are sociopathic bigots (although surely some of them are). Many Trump voters saw him (misguidedly) as an anti-establishment candidate, one who would be a radical disrupter— a disrupter for the unimaginable worse, but a disrupter nonetheless.

The best, most accessible writing about the election that I’ve read so far was by David Klion’s “We Will Never Go Back” in Jewish Currents, where he wrote:

Democrats lost significant ground even in some of the traditionally bluest parts of the country; in New York City, for instance, Trump improved on his 2020 showing by more than ten points, with particularly strong gains in Asian and Latino neighborhoods that matched nationwide trends. With this result, Trump demonstrated definitively that he is liberated from making what many of us regard as sense. Instead, he offered vibes—cruel and vindictive compared with the “joyful” vibes cultivated by the Harris campaign, certainly, but still the vibes that resonated with Americans outside the most rarefied precincts.

Indeed, in gravitating toward Trump, voters seemed to be reading past the candidates’ slogans to identify which party was truly promising to overhaul an untenable status quo…

Once again, it comes down to vibes, reading past slogans. While the most cringe-y of Gen Z-ers tried to convince us that “Kamala is brat,” the truth was that the vibes of the Harris campaign were extremely bad. It turns out that a patronizing genocidal prosecutor is not an especially inspiring candidate, especially one that was not chosen by the people (God forbid), but electioneered in the back doors of party politics.

The individual voters can hardly be blamed. Klion especially mentions the importance of Gaza for the Muslim voters in Michigan, which Harris lost. Bernie Sanders’s statement on the 2024 election got it right, when he lay the blame squarely on the shoulders of the Democratic party:

The Democrats lost because they were unwilling to accept that the status quo is intolerable for most people in this country. It is as if the Democrats were operating in a universe in which 9/11 never happened, in which we could just will ourselves back into the halcyon days of the 1990s, when the flows of capital appeared unfettered, when we thought ourselves, as Fukuyama wrote, at the end of history. It is a truly painful irony that the Harris campaign slogan was “We’re not going back.”

What we shouldn’t do is blame individual people, proclaim the stupidity of Trump voters (or non-voters, or third party voters, who are often the recipients of the most vicious ire), while we pat ourselves on our backs for our superior consciences.

As Klion writes:

The cruel irony is that even as much of the left has sounded the alarm about liberalism’s impending collapse, we will most assuredly be held responsible for it.

What we should do is remember that the results are a structural issue. Those of us living in the United States are living in a dying empire. That dying empire will have enormous ripple effects on the economies and governments of every other country in the world. Our task now is not to turn on one another, but to keep each other safe.

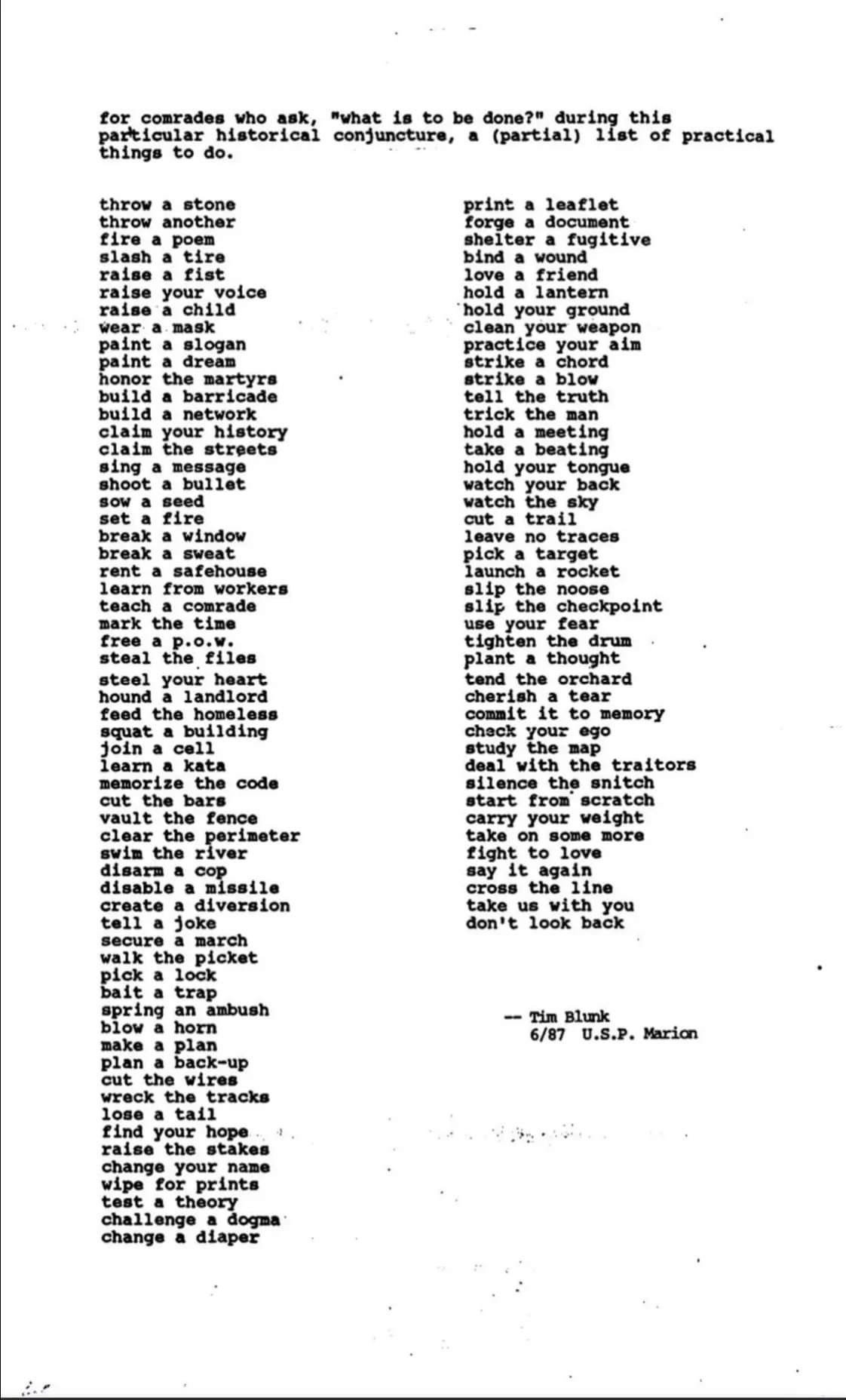

A friend posted this reminder of “what is to be done?” from 1987, whose title stems from Lenin’s famous treatise. It reads almost like a Diane di Prima poem, and reminded me that there is still so much work to do, even (and especially) in the fading embers of empire.